Keep it in the Field

Dear Bubbles,

I assume you take thousands of images. How do you decide which ones to keep and which ones to delete?

~Ed

Dear Ed:

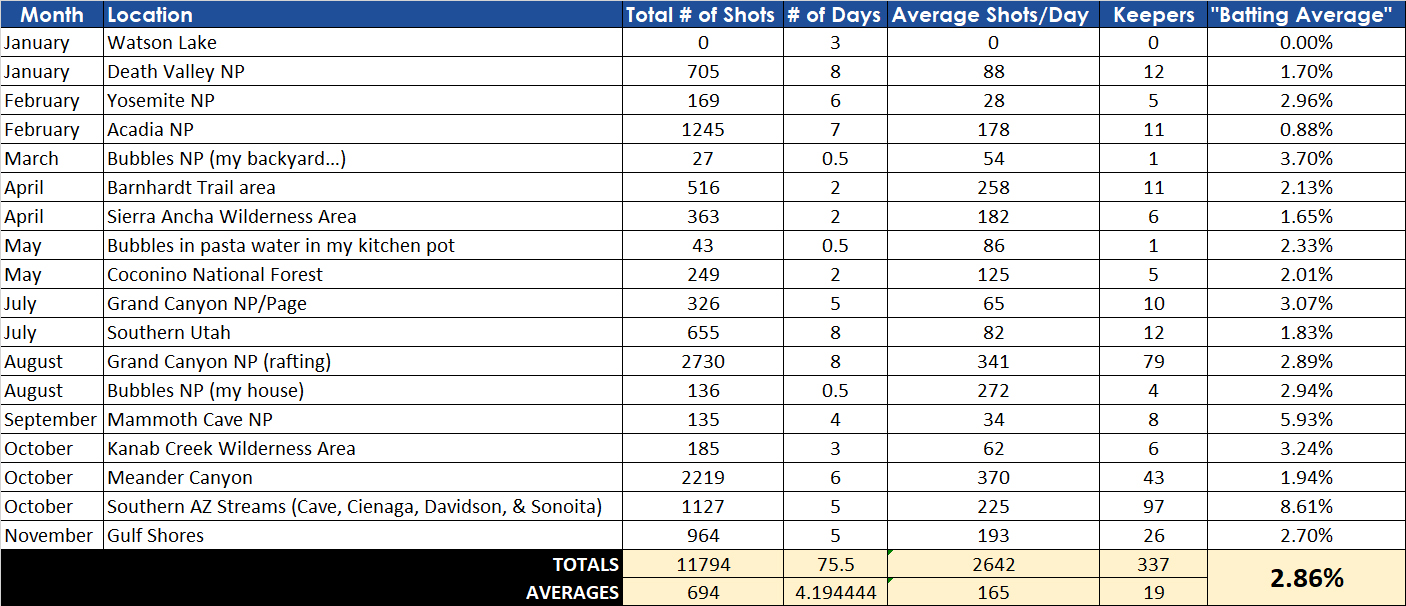

You know how I like data, so I ran some numbers. In 2020, I spent almost 76 days in the field making over 11,794 frames. I flagged 337 of those as “keepers,” meaning I intend to use that photograph for outside purposes like submitting to a magazine or calendar, posting on my blog or social media, using in a webinar or workshop presentation, incorporating into a book, and the like. That means, my keep ratio, what I refer to as my “batting average” was 2.86%.

Here’s the breakdown:

Since there was nothing normal about 2020, I thought I’d compare these results to my 2019 statistics just for fun. Turns out, in 2019, I spent 95 days out and about and created 25,811 frames. I kept 705 of those. Batting average? 2.73%. Cool.

One might respond to such statistics with bewilderment. When I’ve shared similar data from previous years with audiences, I’ve heard, “That’s a lot of bad images to only keep less than 3%!” I remind them of two things:

- Batting .250-.300 will get you into the major leagues in baseball—and keep you there.

- The wondrous landscape photographer Ansel Adams said, “Twelve significant photographs in any one year is a good crop.”

If those are the bars—and I’m not sure they are or should be—I feel like I’m doing A-OK with batting .286 and getting a crop of over 300 images this year. Especially given that I, like others, had to worry about important things like staying alive and finding toilet paper.

That all said, I want to be clear: I pay zero attention to any of these numbers. I don’t come home from a location and count and calculate. I don’t ruminate over them at the end of every year. The only reason I put this chart together was to show that I do, in fact, make thousands of images—and that I keep few of them. Also, I love putting spreadsheets together almost as much as I love seeing bubbles so there’s that.

The good news is, is that no one gives a crap your keep ratio, batting average, or even how many images you make in a year. No one asks. No one looks at your images on Facebook and says, “Wow! What an amazing photograph! I wonder how many frames it took to make that image?” So make as many images as you wish! I just happened to make 11,794 last year. Cool.

With that out of the way, I’ll answer your question about how I decide which ones to keep with a bunch more questions…

This may also surprise you, but I decide which images to keep while I’m still in the field. I do not wait until I see them on my computer. By that time, it’s too late to address any issues I might identify. I spent too many years spraying-and-praying (i.e. mindlessly making a bunch of frames and hoping one turns out) only to see a bunch of poorly executed images on the screen and feel disappointment in keeping none of them. Being mindful in the field changes all that.

When I’m standing in front of a scene, I start by visualizing what I wish to accomplish. Call it goal-setting if you will. I ask myself, “To what am I responding to and why?” The answer to this question becomes the baseline from which I can measure all my future creative and technical choices. Without it, I’d be shooting in the dark. (Pun intended.) Before snapping the shutter, often even before I even pull my camera out of my bag, I define a visual message. Then, as I start changing and pressing buttons on my camera, the question shifts to “Did what I experience come out of the camera?” Sometimes the answer is a quick yes. More often than not it’s no.

When I evaluate the photograph on the camera’s LCD, I ask myself what I like about my image. I do whatever I need to do to emphasize those things within the frame. I also ask what I don’t like about it. I do whatever I need to do to get rid of those things. I make another image, then repeat those two questions over and over for each frame until I get to the point where I can say I like everything about the image (meaning my technical execution matches my desired visual message).

Sometimes it takes just a couple more frames to get things the way I want. Sometimes it takes a lot more. I don’t count, and I don’t care how many snaps it takes to get what I experience out of the camera. So long as I’m learning and not spraying-and-praying, I’m learning with each step. For this process to work, though, one must have a more detailed answer than a simple, “I really like that” or “I hate that.” Understanding why you like or don’t like something will help you determine the necessary adjustments in the field.

Some of the things I look for while I’m doing this (in no particular order):

- Is the composition simple enough? Can I eliminate anything but still retain the context of my intended message?

- Are there any border patrol issues? Border patrol issues are things like out of focus branches, overly bright tones at the edge of the frame, and other unintentional elements that distract one’s eye from the important parts of the frame.

- Is the horizon straight?

- Do any shapes compete for attention? This deals with the relationships among visual elements regarding relative size, proximity, positioning, spacing, etc.

- Is the dominant shape/subject positioned appropriately within the frame?

- Do the visual elements work together to show the illusion of depth?

- Are the lines working together to create a path around the frame and creating shape?

- Are there any mergers—visual elements overlapping—that are distracting or causing too much visual tension?

- How’s the balance between my foreground, mid-ground, and background?

- Is there enough contrast between light and shadow?

- Where does the light grab attention? Is that where I want to draw a viewer’s eye?

- Where is the visual weight heaviest? Is that where I want the visual weight?

- Does the orientation–vertical or horizontal–contribute to my message?

- Are the colors balanced and distributed to support my intended message? Can’t change the colors in nature, but you can balance them within the frame to your liking.

- How does my histogram look? Have I collected just enough light to maximize my data capture (per the Expose to the Right approach)?

- When making multiple exposures for high dynamic range (HDR) imaging, have I captured highlights, midtones, and shadows well enough?

- Is my filter (e.g. polarizer, graduated neutral density, neutral density) helping? Is it obvious I’m using a filter?

- Is the image in focus and is the focus in the appropriate place?

- Is the depth of field enough or too much for the message?

- Have I depicted enough or too much motion?

- When using a wide-angle lens, is the inherent distortion distracting?

- Is this really the story and emotion I wish to share? Is there a different way to convey that message?

- How will I process the image later to finalize my vision? Have I made a good enough image to support those goals?

- Where do I plan to use the image? Different audiences need different types of photographs. A calendar company might need horizontal or square images. The front cover of a magazine is often vertical.

The hard part isn’t asking the questions, it’s knowing how to fix them—and then actually fixing them in the field. It’s knowing moving two steps to the right or left can make a static straight line diagonal and add energy. Or raising your tripod can increase the midground and separate the foreground and background from each other (and lowering it does the opposite). Or slowing your shutter speed leads to more blurred action. You simply can’t get that real-time feedback—or resolution—by sitting in front of a computer screen.

It may seem like a lot of things to think about, especially during fleeting light and everything is moving so fast and OMG QUICK! SHOOT BEFORE YOU MISS IT! (I call this SPP, or “Sheer Panic Photography.”) Keep in mind that I don’t run down this list one by one anymore. I’ve repeated it so much that it’s embedded in my brain, and it only takes a second or two glance at the photo on the LCD to know what I need to do with the next click. If you decide to add these questions to your process, it will feel slow and methodical at first. As with any new skill, though, if you practice enough, it’ll become second nature. I can tell you from experience, panicking doesn’t help anything.

Now, my statistics above may seem to indicate that I’m not very good at this process. Allow me to explain otherwise.

First, most of my trigger counts around moving water can be attributed to shooting in “machine gun mode”—i.e. continuous shutter mode—while tracking just the perfect wave, lighting conditions, movement, etc. When I’m around the coast, waterfalls, and bubbles, I make thousands of frames both because I’m trying to learn how to get the arrangement just right (the perfectionist in me) and because I’m having the time of my life marveling over what nature does. Consider how much joy I get out of photographing bubbles for an hour. You think I’m gonna just make one frame of bubbles?

Second, I also ask a lot of “what if…” questions in the field to push my creative and technical skills. I play and experiment constantly which means yes, I make a lot of images that don’t turn out to my liking. But in doing so, I refine my tastes and techniques for what I do like. That’s progress! Besides, it’s unreasonable to believe that all our trials will come out successful. And to put pressure on yourself and expect that they do will only lead to frustration. Photography is supposed to be fun, remember!?

There are times when the answer to the did-what-I-see-come-out-of-my-camera question is no, no, no, hell no, no, no, no, no, no, no….when things aren’t working out, don’t get frustrated. Ask more questions. Keep learning. Keep feeding the creative process. The question to ask at this point is “Are you having fun?” If so, keep going no matter the end result. (This is called an autotelic personality.) If you aren’t having fun, stop and find something else fun to do.

Once I get to the point where I like everything about my photograph, I tap the AEL/AFL button on the back of my camera to protect that frame. A key icon shows up in the top right of my LCD when the photo displays and later in Adobe Bridge. I think it’s intended function is to prevent the image from getting accidentally deleted. I use it, though, to signify that THIS is the frame I wish to keep when I see it, among the thousands, on my computer screen. This is much easier than trying to remember file numbers or picking it out of a line-up with nothing but visual cues.

For the most part, by the time I get to processing at home in front of my computer, I already know which images I plan to invest time in processing to a final state for consumption. Processing is one of the last steps in bringing my vision to life, though, not the beginning. Generally, if I didn’t like it in the field, making it bigger on the screen to emphasize its flaws isn’t going to change my mind.

That’s not to say I don’t change my mind occasionally. I don’t always keep everything I thought I liked in the field. I also find a few “gems,” images I like on the computer screen, but for some reason, didn’t like in the field. This is usually a function of being too hard on myself…sometimes I’m too picky…I’m working on it…

I don’t delete many of my images. I retain even the ones I don’t mark as “keepers.” Sure I delete the obvious screw-ups. Sometimes I find gems years later in old files, though, usually while I’m searching for images to support a submission. As we expand and mature our technical and creative knowledge and skills, it’s not unusual to look at something old with fresh eyes and apply new ideas.

The only real downside to holding onto a bunch of images is having the need to buy a bigger portable hard drive to store them all–a small sacrifice to give myself opportunities down the road. I mean, like frames, no one asks how many hard drives you have when they look at your image on Facebook. I’m not even sure how many of those I have, but you know how I like data…

Be well, be wild,

Bubbles

Have a question about photography and/or the creative life? Need some advice? Looking for inspiration? Send your question to Dear Bubbles at colleen@colleenminiuk.com to be possibly featured in a future column post. (If you’d prefer a different display name than your real first name, please include your preferred nickname in your note.

2 Comments

Cynthia D Hollingsworth

Dear Bubbles, I really, really liked this post — not that I haven’t with other ones, but you struck a lot of chords in me with this one. I would go bonker crazy if I had to keep (or create) a spreadsheet like that — but I respect people like you who can and do.

I know that I need better discipline in the field. I tend toward “look, there’s a squirrel I like.” Later, I think — oh, I should have put on my filter and by then it’s too late. So I LOVE the list of your questions. I will admit that I think I would feel like a dork if I pulled out my printed list before every shot in the field. I think that much of my issues is that I don’t shoot enough — since it’s not my job right now and there’s a lot of life interference, I think that I spend a lot of time re-learning the finer details once I’m in the field. As long as I’m employed full-time, I think that may continue to be an issue — if you know or feel otherwise, I would love your insight.

A question for your work flow — do you ever delete images from the card in the field? I’ve heard people say they do discard obvious goofs, but from a long-standing computer career, I thought that would lead to the FAT becoming problematic.

Thanks for being such a great role model and shooter and sharing your journey.

Bubbles

Thanks so much for all your kind words, Cynthia! Means a lot to me, I appreciate all your support now and over the years.

Know that I carried printed depth-of-field charts for two years (!!!) into the field. I couldn’t have cared less what I looked like (most definitely a dork!). I was learning! So if you feel like printing the questions out will help you, go for it! It’s not your problem if others have an opinion about YOUR work. Who cares?!?!

I love your other questions, and in fact, both are great future Dear Bubbles posts.

In short, there’s A LOT going on in the world right now. We may feel like we’re pulled in a million different directions. One thing you can do if you can’t escape to make photographs is visualization, dry shooting specifically (pretending like you’re making a photograph without touching your camera and traveling to the field). You can visualize anywhere, anytime! And visualization is known to be as powerful as actually practicing.

As for deleting images, no, I generally don’t delete off my card directly since it leads to a degradation in the card. I reformat after downloading my images to my hard drive, since that serves as a “deep clean” on the card.