Planning to Not Plan

Dear Bubbles:

How much planning do you do before you go on a photo shoot?

~Doug

Dear Doug,

Because it’s fresh in my mind and representative of how I plan for most of my outings, I’ll offer how I approached my trip to the Kanab Creek Wilderness Area just last week:

On my annual Grand Canyon rafting photography retreat, we follow the same logistics for our take out every year. It takes two flights to get our group out of the canyon from Whitmore Wash (mile 188) back to Marble Canyon near where we start the trip (at Cliff Dwellers Lodge). First, a helicopter whisks us from the river to rim. After a seven-minute ride, we land at Bar 10 Ranch on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. Then, we board a prop plane for a 45-minute ride to a small landing strip in Marble Canyon.

From what I can discern, the helicopter traces almost the same path up the canyon and across the from year to year. The plane takes a different route each time, though. Sometimes we approach Marble Canyon from the south, closer to the rim of the Grand Canyon over the Kaibab Plateau. Other times, we fly in from the north across the Paria Plateau and the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument. (I’m not a pilot, but I presume wind, temperature, weather, other planes, and other factors determine the flight path…)

This past August, our pilots flew south, closer to the edge of the canyon than on previous trips. I scored a window seat on the south side which meant I had a birds-eye view of the Grand Canyon, numerous side tributaries, the Kaibab Plateau, and House Rock Valley en route to Marble Canyon. Midway through the flight, I spotted a clearing overlooking an impossibly beautiful sprawl of rocks where two side canyons converged and met the Colorado River in the distance. From what I remembered seeing on the river and on my river map, I thought it was Kanab Creek Canyon. I made a mental note to look it up later when I returned home.

And that’s exactly what I did. I immediately brought up Google maps and retraced our flight path until I found the clearing above the confluence of Kanab Creek and Jumpup canyons in the Kanab Creek Wilderness Area. Now I needed to figure out how to get there in my truck and camper…

I followed the lines of roads from that spot back to the main road, Highway 89A. Once I knew what path to take, I did a fresh Google search on each of those tracks to determine the road conditions. Were these 2WD or 4WD roads? Were they maintained? Were they rocky or sandy or steep or flat? In other words, could I get my truck back there, and if so, how long might it take? I’m a map fanatic. I can–and do, and did!–spend hours and hours going down the rabbit hole of endless possibilities and “what if…” scenarios (e.g. “What if I took that road? Then that one? Then THAT one!”

After I pulled myself away from different colored lands, topo lines, and the spiderweb of roads going to places I’d never been—but could!—I also brought up information about the Kanab Creek Wilderness Area to learn about any permitting requirements, entrance fees, and dispersed camping limitations. No permits, no fees, no limitations. How soon could I go?

I had some free time last week (thanks to the pandemic cancelling my annual Acadia National Park trip in October). I pulled up the weather forecasts for that general region on my weather apps, Dark Sky and Windy. Low 80s F for the daytime temperature and high 40s F for the nighttime temperatures seemed like perfect camping weather. I monitor weather only to decide what kind of clothes to pack, not to determine the lighting conditions for photography. I mean, I’m not going wear shorts if I’m headed to Mount Everest….Anyhow, I go rain or shine and try to make the most of whatever Mother Nature dishes out photographically-speaking. I don’t wait for light (and the light doesn’t wait for me either, as it turns out).

I also consulted The Photographer’s Ephemeris and Google Earth to visualize the type of light I would see from that point. In both apps, I navigated to that spot and typed in the date of my proposed trip. I noted the time and angle of the sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset.

I started visualizing photographs I might make once I arrived, blending my recollection of what I saw out of the plane window in August with how the light and shadow might fall across the scene. To get new ideas to feed my visualizations, I googled “Kanab Creek Wilderness Area” and sifted through the resulting images. Most of what turned up on the internet looked like snapshots, but nonetheless, they offered plenty of additional information my imagination could use in a variety of additional “what if” scenarios. What if it’s clear and sunny for the duration of my trip? What if it’s overcast? What stories will I tell visually and how? What broad scenes might I photograph? Details? What if I stood on the east side of the point? The west?

Ansel Adams called this practice “dry shooting.” It’s where you design photographs in your head without a camera in your hand. Research shows the more specific you get with your visualizations through all your senses, the better. I define my photograph as specifically as possible, down to the lens, aperture and ISO settings. (If I’m shooting rocks or other elements that aren’t moving, I don’t care a lick about my shutter speed setting. It is what is it…). Australian psychologist said, “…the most effective visualization occurs when the visualizer feels and sees what he’s doing.”

During my pre-trip visualization phase, I make everything up about my imagined photographs—conditions, settings, positions, perspectives, everything. I’m fantasizing. I have no idea what will transpire “out there” when I arrive at a location. I’m training my brain, creating muscle memory, so that I’m quicker to respond to spontaneous moments on location. As Louis Pasteur said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Besides, if you can’t be in the outdoors, it’s sure fun to daydream about.

When the date I had picked out arrived, I packed my truck and off I went to find the place I spotted from the airplane months earlier. Had I not already been studying and reading about the Grand Canyon geology, geography, flora, fauna, and other people’s personal experiences ahead of my river trip, I would have ordered books on all those topics. I would have watched online videos and documentaries as well ahead of time. I seek to know what’s special about this place? What might I see and experience? What’s getting me excited about this area and subject matter? This helps not only feed additional photographic visualizations, but it also starts to build a personal connection which drives more personally-meaningful images later.

(I should note here that now that I’m back from my adventure and know more about this fabulous place, my excitement ad curiosity will continue to lead me to gain more information about it through books, videos, etc. Learning never ends for me.)

After driving 9.5 hours and 400-plus miles one-way, which included two detours (one due to wildfire closures, one due to deep sand) and about 10 miles on a rocky two-track that threatened to pop tires, I made it to that clearing on the cliffs above the confluence of Kanab Creek and Jumpup canyons. No amount of planning could have captured my emotional response to it. The view was even more glorious than I had seen from the plane.

Along the way, I stopped planning. I stopped thinking about photography and what if scenarios and dry shooting. I tossed all expectations of what I may see and judgments of whether it’ll be good or not to the wind out my window. Zen Buddhists call this mental state where your mind is free of expectations and judgment “mushin.”

This means I don’t go on dedicated “photo shoots.” I don’t visit places with the intent to make photographs. Instead, I set out on outdoor adventures—camping, hiking, standup paddleboarding, etc.—and my camera simply comes with me to help me record memories and tell visual stories as I go. I didn’t go to Kanab Creek Wilderness Area to photograph. I went to explore and discover.

In this vein, no matter how much planning I’ve done ahead of time, when I arrive to a location:

- I have no expectations of making an image. As Dorothy Lange said, “To know ahead of time what you’re looking for means you’re then only photographing your preconceptions, which is very limiting.” Instead of setting out to photograph, I continue to fill my brain with knowledge and ideas (the first step in Wallas’ Model of Creativity) trusting that the “aha” moment (the third step in Wallas’ Model of Creativity) will occur at some point. I’ll sit with a bottomless cup of coffee and study the light and shadow as they crawl up and down the shoulders of buttes and spires. I’ll hike in every direction. I’ll pull the map out to learn the names of prominent features while they sit in repose in front of my eyes (and lose hours and hours…). All in an effort to understand what’s happening right now in this particular spot. Getting to know my surroundings is my only expectation I have for myself on an outing, whether I’ve never been to a location before or I’ve been there hundreds of days. (Wait, I take that back. I have a two other expectations: one, have fun, and two, don’t get hurt.) Only when I feel moved or excited do I even think about picking up a camera. Then…

- If I happen to make an image, I have no expectations that it’s a good one. To aim to record a usable for public consumption in social media, galleries, exhibitions, books, and presentations or for sales to editorial outlets, calendar companies, or prints to private clients puts too much pressure to perform on me. Besides, how well could you know a place on your first visit? Think about it: how well do you know a person when you meet them for the first time? You don’t. Now, that’s not to say you can’t or won’t make a meaningful image on the first try. You might get lucky with light and composition. But I find I make better images (i.e. images I’m proud of that represent my experience) after I know more about a subject or location.

I realize I am fortunate to have the flexibility to revisit locations over and over again—which makes it much easier for me to accept I may not come home with any images, let alone good ones. Sometimes I do, as I did with Kanab Creek Wilderness Area. Sometimes I don’t. And I’m a full-time photographer!

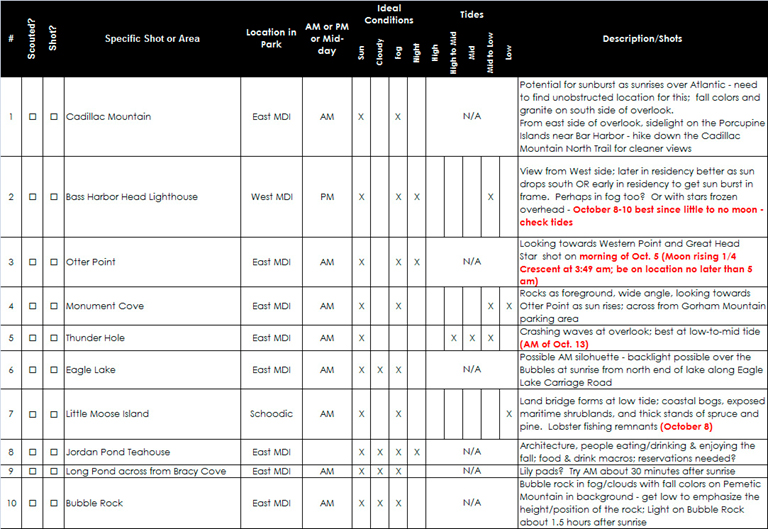

Those practicing photography as a hobby and outlet from their full-time jobs, however, do not always have such luxury. I know, I’ve been there before. When I worked as a software engineer/project manager at Intel, I used to create spreadsheets of visualized images. (Yes, I planned software development projects for a living for almost eight years. I also planned my wedding on a gantt chart. I’m not great at a lot of things, but I know how to plan things…)

I’d bring the spreadsheet into the field to use as a checklist. Sure, it’d get me into the “right” place frequently, but not necessarily the “right” time. I never seemed to get the shot I wrote down. I remember getting so frustrated and disappointed when things didn’t go the way I planned. I mean, I had worked so hard in figuring it out! Why couldn’t things just go the way I want? Waaahhhh!

It took me some years of feeling more dissatisfaction than I’d like to admit before I learned to accept that the Universe does not entertain my requests. It didn’t care one iota that I took the time to plan out that perfect shot with the perfect light in the perfect place. It cared not that I wanted a fiery sky, crashing waves, and no wind. I didn’t stop planning and visualizing, though. Let’s be honest, I love planning and visualizing. I simply released the expectation that I’d “get the shot” just because I wrote it down on a spreadsheet ahead of time.

If the idea of ditching your visualized ideas once you’re in the field seems odd or even wasteful to you, consider this: do you make a list of things you need to buy at the grocery store? If so, that’s a visualization. What happens when you get to the grocery store, though? Blackberries weren’t on your list but dang, they sure look tasty. Oh and your favorite wine is on sale right now. And bubbles! You forgot to put bubbles on the list! But now that you see them, into the cart they go. You may find everything on your shopping list, but it doesn’t limit you. (If it does, you have way more control when it comes to blackberries and wine than I ever will…).

Planning and visualization can help you mentally prepare for your photographic outings, but don’t become a slave to them. My photography practice became way more fun and productive once I shifted my attitude towards embracing, not trying to control, uncertainty. Control is an illusion anyhow. There are simply too many factors and variables to make any outcome–planned or not–unpredictable. Letting my brain do its mental work while I focused on relaxing, observing, and soaking in my surroundings, though, required me to hold onto confidence in my own technical abilities, that I was not only capable of responding to spontaneous situations Mother Nature threw at me, but I made better images, images I was proud of and that meant something to me, when I did.

From my adventure to Kanab Creek Wilderness Area, I was thrilled to learn much about the area (including on the drive in and out from the point), to spend time marveling over the spectacular panoramic view, and to come up with more questions than answers about this geological wonder. I made a handful of images I’m proud of too, which was simply a bonus to an already amazing experience.

Now, all this said, there are many occasions when I’m out and about and decide to take a spontaneous left-hand or right-hand turn that leads me to a location I never intended on being. Those experiences are frequently the most memorable (and perhaps the most hilarious…). I mean, really, who needs a plan or a spreadsheet so long as you have bubbles, blackberries, and wine?

Be well, be wild,

~Bubbles

Have a question about photography, art, and/or the creative life? Need some advice? Looking for inspiration? Send your question to Dear Bubbles at colleen@colleenminiuk.com to be possibly featured in a future column post. (If you’d prefer a different display name than your real first name, please include your preferred nickname in your note.