Playing Favorites

Dear Bubbles:

It’s your brother. Which of your photographs is your favorite and why? Is it your favorite because of the adventure you had, your camera equipment and settings at the time, the location, the people you were with, or something else?

~Rob

Dear Rob, my favorite (and only) brother:

To help me answer this question, I asked Mom and Dad, “Between Rob and me, who is your favorite child?”

Mom quickly said, “You’re our favorite, of course.” Dad nodded his head in agreement. I knew it!

Mom continued, “….you’re our favorite daughter. Rob is our favorite son. We love you equally for different reasons.”

We have the best parents, Rob. It’s hard to argue with their answer, especially since it also sums up how I feel about my images. I love all my photographs for different reasons.

Over the years, I’ve had varying motives for making a photograph: because it was the moment I finally understood hyperfocal distance; because it was the first time I tried a new technique; because it was the 457th time I photographed bubbles, and it still made me smile; because something made me laugh, or made me cry; because a piece of gnarled driftwood reminded me of a flame; because a rock looked like an alien; because the storm brewing inside me felt like the one brewing “out there;” because a moment evoked memories or caused excitement about the future; because it felt incredible to experience a moment of awe and wonder I never wanted to forget, one that I’ll likely never experience again; because an experience enriched my life, or because it enriched someone else’s life; because making the image was fun; because I just felt like it. Each photograph I make represents a significant moment in time for me, one I deliberately noticed and wanted to preserve and possibly share with others. It’d be impossible for me to pick one over all the others.

But…well, there is this one…

In late October 2013, Mom, Dad, and I visited a remote section of Acadia National Park on Isle au Haut in Maine. I had never been there before, but wanted to include key locations in my guidebook, Photographing Acadia National Park, The Essential Guide to When, Where, and How. On the first day of our visit, we ventured to the Eben’s Head Trail well before sunset to allow extra time for exploring the unfamiliar area.

After a short meander through the forest, we emerged onto a ledge high above the rocky coastline, where cliffs hugged small coves of cobble, driftwood, and other detritus. We decided to take a closer look at the small tide pools on the volcanic rock below, remnants of a receding tide that provided a fleeting glimpse into an otherwise hidden ocean world.

We scrambled down the granite ledges to reach the protected cobble beach. Dad ventured to a large piece of driftwood to rest and soak in the beautiful view of waves and the endless ocean. Mom, who was hiking a few steps in front of me, climbed onto a large outcropping of volcanic rock. She suddenly stopped and bent over a small pool no bigger than two feet in diameter and maybe six or eight inches deep. “Hey, Colleen! Come here! You have to see these bubbles,” she said.

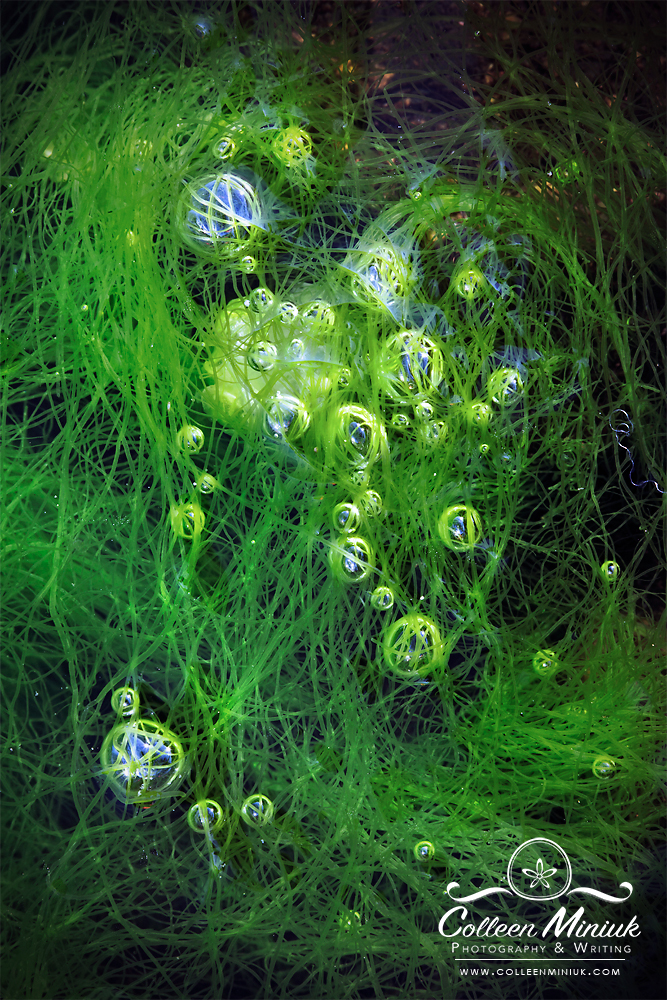

I scrambled over to her and peered into the hole. Immediately, my vision tunneled. My surroundings disappeared. I didn’t just see a tangle of green seaweed and floating bubbles. I saw an entire universe of planets and galaxies spiraling right in front of my eyes. I was mesmerized. I knew I had to make an image of it.

I walked around the scene to begin visualizing how to shove an entire cosmos into a rectangular frame. I settled on a vertical orientation based on the bubbles’ arrangement and the swirling feeling I wished to convey. I kept my lens parallel to the surface of the water so that the face of the bubbles and the top layer, at least, remained in focus. That meant positioning my camera directly over the top of the scene looking down. A small aperture, f/18 I decided, on my 100mm macro lens provided adequate depth of field. The backlight from the late afternoon sun not only highlighted the bubbles, but also created a dark backdrop. I remembered to check my polarizer, twirling it just enough to get a little reflected blue light from the sky in the bubbles. Then CLICK! The image above resulted. I titled it “Another Universe.”

I showed my mom the back of my camera and squealed. “This is THE best photograph I’ve ever made in my life!”

“Oh wow!” Mom said, nodding her head and hugging my shoulder. “Absolutely.”

“What are you two doing over there?” Dad said from his driftwood throne some 30 feet away.

“Dad, I just made the best photograph I’ve ever made,” I said, smiling proudly.

“What? No way,” he said. “I don’t even know what you two are looking at. Let me see.”

I took my camera off my tripod and walked down to my dad. He studied the back of my screen. After a few seconds, he looked up. “Oh yeah, that’s definitely the best photograph you’ve ever made.”

He looked at it again, “But what is it?”

“It’s another universe, Dad!” I said and then explained the literal components.

I single out this moment and image for a specific reason– and not because I believe that it was the best photograph I had made up to that point. It has nothing to do with quality. Instead, this image represents a critical inflection point in my photography approach. I highlight it because, beyond the content of the photograph, it holds important learnings that I never want to forget.

Before this moment, I actually didn’t like many, if any, of my photographs. In part, it was because I wasn’t technically competent enough with photographic concepts or with my camera to truly capture what I was feeling or experiencing in a moment. I also didn’t know how to express my own voice. Hell, I didn’t even know I had a voice. I photographed what I thought I should photograph based on what I saw in calendars, postcards, and magazines, so I spent most of my time chasing iconic shots in “good” light (a.k.a. a colorful, fiery sky) regardless of how I felt about them. In time (and by that I mean a lot of time, like 12-years time), I eventually developed technical proficiency and a repeatable process for creating salable landscape images. I should have felt overjoyed, right? I didn’t. I felt unfulfilled and frustrated. Honestly, I was bored out of my mind.

When I made this photograph on Isle au Haut, it was the first time I had fallen completely head over heels in love with a scene. Not liked, loved. Like teenage drunk in new love, losing all two of my marbles in my brain, loved. Now, if the scene or subject doesn’t turn me on, I don’t turn on my camera. Yes, I’m that picky. Why waste time on things you like (or don’t like)? It only prevents you from experiencing and photographing what you love. If you want your photographs to express emotion, you have to feel those feelings first then compose accordingly.

It was also the first time I had created something entirely on my own, not through copying other people’s compositions in different weather conditions, light, or seasons. And I hadn’t consciously forced it to happen. In hindsight, it took almost two years for this photograph to come together. I had been shooting seaweed and bubbles separately on coastlines, rivers, lakes, and puddles–never successfully, in my opinion. This image came together because my brain put the two concepts together when I saw the scene. My brain created the “aha” moment for me. It was utterly delicious.

The process of blending existing ideas–seaweed and bubbles, for example–into something new is called, “conceptual blending.” Conceptual blending isn’t limited to photography. It happens everywhere. Your iPhone or Android is a perfect example of this concept. We had phones before these ever existed. The internet, music players, and calculators too. Innovators simply put them together to create something we can no longer live without.

See, creative experts believe that creativity comes from the combination of existing ideas, not from thin air (as it often seems). It may, then, come as no surprise that the first step in the Wallas Model of Creativity is “Preparation,” or as I like to call it, “Filling your brain with knowledge and ideas.” As Jack Turner, author of How to Get Ideas, said, “…if ‘a new idea is nothing more or less than a new combination of elements,’ then it stands to reason that the person who knows more elements is more likely to come up with a new idea than a person who knows fewer old elements.”

Before I made this image, it hadn’t occurred to me to trust the creative process, to trust that my brain would take my existing knowledge and connect it with different scenes and subjects. I had been planning for certain types of weather, forcing compositions based on the so-called rules, and getting frustrated when I made crappy images. Turns out, I didn’t have to try or work so hard. As one of my friends in junior high school used to say to me when I got overly excited about something, “Girl, calm your bad self down.” If you’re a Star Wars fan, as Yoda said, “Patience you must have.” (I tried to write that in my best Yoda voice, but I think it came out more like a frog…) Anyhow, I realized with this image that if I just kept feeding my brain knowledge and ideas, it would subconsciously help me make images as I explored and experienced the world.

Now I spend more time collecting inspirational elements than I do photographing. I only check the weather to determine what I need to wear on my escapades, not to determine whether I’ll go outside (that’s always a “yes”). I compose based on human perceptions not rules. Most importantly, I embrace my failed photographs (and I have A LOT of those), knowing they serve a very important part of the creative process. If I hadn’t photographed seaweed and bubbles separately and unsuccessfully for two years, I’m convinced I would have never picked this scene out on Isle au Haut.

My “failed” frames excite me now. I’m serious. It’s evidence I’m trying to push beyond what I already know works. It’s an opportunity for me to learn what I like and don’t like. It’s my chance to train and prepare my brain for the future, and I can’t wait to see what it puts together for me down the road. As Thomas Edison said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Finally, this photograph represents the first time I had enough confidence in my technical abilities, my execution, and my own interests to proclaim my love for this scene outwardly. I had enough confidence to say, “You know what? I LOVE BUBBLES!” I didn’t care then, and I don’t care now, if anyone else in the world loves bubbles. They fill my soul with joy every time. And that’s why I pick up a camera in the first place.

So the moral of the story? Be curious about the world. Work towards technical proficiency so you can effectively translate what you experience into your photographic frame. Embrace failure. Trust the creative process. Exercise patience in your approach and exude confidence in photographing whatever it is you LOVE (not what you like), regardless of what other people think. Do all that, and you won’t have to pick favorites. (You can if you want–remember from last week’s post, you do you). You’ll come to love all the images you make. They’ll all mean something to you.

Be well, be wild,

~Bubbles

Have a question about photography, art, and/or the creative life? Need some advice? Send your question to Dear Bubbles at colleen@colleenminiuk.com to be possibly featured in a future column post. (If you’d prefer a different display name than your real first name, please include your preferred nickname in your note.)

4 Comments

Claude Hamel

Very nice piece. Speaks to me! Best for the holiday season!!

CH

Bubbles

Thanks, Claude, for the feedback. Happy holidays to you as well!

Alicia Glassmeyer

I love this! The image is stunning but the message is so inspiring. I still struggle with loving my images. I am right where you said you were previously with thinking I need to be calendar perfect like all the other images you see online.

Thanks for sharing!

Bubbles

Thanks, Alicia. Photographs need not be “calendar perfect,” they only need to be expressions of YOU. If you LOVE calendar perfect, by all means, keep photographing the way you do. If you like or don’t like calendar perfect, stop and photograph something else you LOVE. In my opinion, we see plenty of calendar perfect. I want to see Alicia Glassmeyer because no one else, absolutely no one, can show me what you see and experience in the world. And that makes whatever you do photograph YOU perfect.