Keeping it Fresh

Dear Bubbles:

I feel stuck. I’ve been fortunate enough to travel to and photograph many beautiful places, but lately, when I visit a spot, I just don’t feel inspired to take any photographs. Is there something wrong with me? What can I do to get excited about photography again?

~Jim

Dear Jim:

I’ve experienced those same feelings before—on multiple occasions and to varying degrees. The first time I felt uber-bored with my photography was in 2009. I followed the advice of a mentor, who suggested I should run around the Southwest and make images of all the iconic scenes, only differently, in order to get published more frequently. I sold a lot of images in doing so, but I was bored out of my mind. My compositions were unoriginal. The light and weather never seemed to cooperate how and when I wanted it to. I didn’t like many, if any, of my images I produced.

As luck would have it, I happened upon the National Park Service’s Artist-in-Residence program about that same time. I applied for a residency in Acadia National Park and was accepted. I explored the park for the first time in November 2009 for three weeks. I fell so in love with the place that I applied for a second residency—and got it, this time in October 2010. I fell more in love with the place during those three weeks, so I applied for a third residency—and got it for January/February 2013. They couldn’t get rid of me!

During first week of the third residency, I found myself on the coastline doing exactly what I had been doing for years in Acadia, around my home in Arizona, and in other places around the country: setting out only at sunrise and sunset; waiting for “good” light (i.e. colorful skies); using my wide-angle lens set to ISO 100 and f/22 with a three-stop neutral density filter; and strictly adhering to the Rule of Thirds. One day, I felt frustrated when I couldn’t find an appropriate foreground as the sun began to rise. I stopped, took my camera off my tripod, and quickly snapped the frame you see above. I said to myself, “Great. Another image of Acadia. Is this all there is to photography?” Once again, I was bored out of my mind. After spending, at that point, about 150 days in Acadia, I had run out of ideas. And I had three weeks left of my residency…

Psychologists Jerome Singer and Michael Barrios conducted a study on writer’s block in the 1970s when they determined four primary causes of why we feel stuck:

- Excessively harsh criticism

- Fear of comparison to other people

- Lack of external motivation (like attention and praise)

- Lack of internal motivation (like one’s interest in telling one’s story)

In hindsight, I felt uninspired in Acadia because I didn’t think I was making particularly exciting images. Salable, yes. Moving, no. I also didn’t feel like I had anything left to say. In fact, I wondered if I had been to Acadia too many times (which I now know is an utterly absurd sentiment). Check the boxes for numbers 1 and 4 above. So what to do about it?

On the opposite side is what psychologist Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi called “flow.” He suggests in his research that people are happiest when they experience the blissful mental state where they are, “…completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz.” If you’ve ever felt like you’re in the zone, like everything is effortless, and magic is happening, you’ve experienced flow.

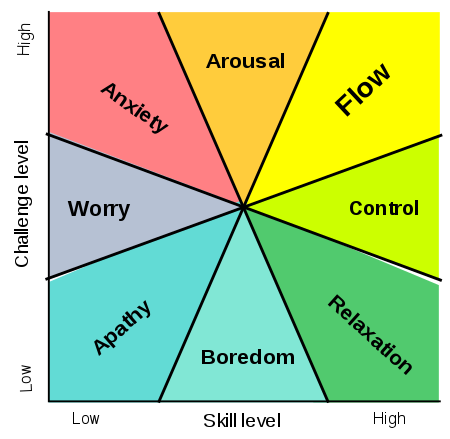

Csíkszentmihályi offered a framework, the Experience Fluctuation Model, which describes how a balance of skill level and challenge level affects the types of emotions we’re likely to feel as we navigate our activities:

Researcher Owen Schaffer proposed that in order to get into a flow state, we must know three things:

- What to do

- How to do it

- How well you are doing at it

In other words, the goal of an activity must be clear, you have a certain set of skills to perform such a task, and you can measure your progress toward that goal in some way. Shaffer also indicated that we must free ourselves from outside distractions while engaged in the activity, which must combine a high level of challenge that puts just enough demand on our skills. According to Csíkszentmihályi’s Experience Fluctuation Model, an endeavor that combines too steep of a perceived challenge can lead to anxiety. One that isn’t challenging enough can lead to apathy, boredom, or relaxation, depending on your skill level.

Flow is a nirvana state for artists, but how do we get ourselves into this heavenly zone with our photography, especially when we feel like we have obstacles preventing us from getting into this state? How do we get unstuck? And is it really reasonable to stay in a state of flow all the time?

As you can see in Csíkszentmihályi’s graph, boredom is a normal part of the creative cycle. So is apathy and anxiety. As our skills develop and we put ourselves into new challenges, we’re apt to bounce all over this model and experience all of these emotions—not just flow. Attitude and acceptance of this can go a long way in freeing yourself and redirecting your energy into more productive directions.

When I think back to that moment in Acadia, it’s no surprise I was bored. I had reached technical proficiency (so I deemed my skill level as “medium”) and my challenge level was low. My guess, Jim, is you’re somewhere close to this on the spectrum with your own work. This in it of itself isn’t a problem. The issue comes in when we believe we should feel overjoyed, then feel frustrated when we don’t. As Dale Carnegie said, “It is the way we react to circumstances that determines our feelings.”

In addition to holding onto a more encouraging attitude, we can also take ownership of continually developing our capabilities. If we take steps, even small ones, toward achieving proficiency in our photography, we put ourselves in a better position to experience a flow state. Besides, learning is fun! And endless! Think of all the things that go into making a photograph, like camera functions and features, photographic techniques (e.g. exposure, histograms, depth of field/hyperfocal, focus stacking, HDR), accessories (e.g. filters, flash, reflectors/diffusers), composition and visual language, processing and image management, and printing/output. I’m pretty sure it’ll take me a lifetime just to figure out all the menu items on my camera alone!

If the only thing we do is focus on improving our skills, though, the best we can hope for is Relaxation according to the Experience Fluctuation Model. If we keep our challenge level high, though, we can fall into the “Anxiety-Arousal-Flow” possibilities. And if we know anxiety is coming, we can manage it through our attitude.

When I realized how bored I was in Acadia in winter 2013, by happenstance, my brain wandered to an unforgettable experience I had during my second residency. At that time, I helped to establish the Photojournalism class for the Schoodic Education Adventure—a residential education program for 4th-thru-8th graders where they learn about art and science in Acadia’s natural classroom.

While leading a group of fourth graders through the forest on a photo walk for the course, a young boy in my group suddenly lost his marbles. He kept repeating, “LOOK AT THAT MUSHROOM!” In his mind, he had found the coolest fungi on the planet. He then looked up at me and said matter-of-factly before snapping a single photograph, “I think I want to be a photographer just like you when I grow up.”

My heart melted when he said this. Recalling this moment later during my third residency, though, I cringed. That little boy thought, that as a photographer, I did what he had just done, all the time. He thought I ran around the forest with unbridled joy, photographing whatever it was that sparked my emotions. I didn’t do anything of the sort. I was stuck in my same old photographic habits trying to take a technically perfect picture of an iconic scene at sunrise and sunset with my wide-angle lens set to ISO 100 and f/22 and using my three-stop graduated neutral density filter.

I asked myself, “What if that is how I started approaching things with my photography? What if I ditched the idea of accomplishment and replaced it with curiosity? What if I made images simply because I enjoyed the experience and did not care about the results?” I had nothing to lose by trying. A new challenge!

Pablo Picasso said, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” With due respect to Picasso, a solution to this “problem” exists: approaching your scenes with a beginner’s mind, or “shoshin” in Zen Buddhism terms. This philosophy suggests one should release expectations and preconceptions in favor of openness and enthusiasm to learn, as if you were experiencing everything for the first time. As Shunryu Suzuki wrote in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s mind there are few.”

Creative photography need not be a means to an end. We can approach our outings with an autotelic personality, which Csíkszentmihályi describes as pursuing “…a self-contained activity, one that is done not with the expectation of some future benefit, but simply because the doing itself is the reward.” Instead of pressuring yourself to make an image, you simply enjoy the moment exactly as Mother Nature presents it, embrace the process of making an image, and unleash your curiosity about the world around you.

I did just that. I ventured into Acadia with renewed enthusiasm and played like a fourth-grader. Only when I got excited about a subject or a scene would I create an image of it. And oh, how the ice excited me! The various types of ice—frazil, grease, pancake, and more—collecting on the water’s edge captivated me. I watched the ocean freeze into an ice shelf at high tide. Then watched it crash at low tide onto boulders and create formations I termed “ice volcanoes.” While walking in the parking lot atop Cadillac Mountain, I saw ice bubbles and lost my marbles, yelling aloud despite my solitude, “LOOK AT THOSE ICE BUBBLES!”

After three days of this, I felt emotionally and physically drained. Playing like a fourth-grader was exhausting! Trying to find my own compositions was time-consuming and hard. The images I had been creating were horrible, embarrassing even. Instead of giving up, though, I decided to keep playing. After all, I was enjoying the process of making images far more than I ever had.

For the next two weeks of my residency, I made the worst images of my life. But they were finally mine, not copies of what others had already done. They were my very own creations that represented the subjects and scenes that meant something to me in my unique journey in Acadia. A critical transformation was underway, one where I was moving away from a person who liked to take pretty pictures and into becoming a visual artist expressing myself in more personally meaningful ways. As author Cynthia Occelli said, “For a seed to achieve its greatest expression, it must come completely undone. The shell cracks, its insides come out and everything changes. To someone who doesn’t understand growth, it would look like complete destruction.”

In this short awkward phase, I gave myself permission to fail. I ignored my normal negative self-talk. As I talked about in an earlier Dear Bubbles post, The Art of Not Sucking, criticizing yourself comes from unrealistic and unfair internal expectations that you should be farther along in your journey than you are. Wherever you are, you’re right where you’re supposed to be.

Keep in mind that when you engage in a high level of challenge, one that pushes your skills beyond your comfort zone, chances are good that not all your ideas or attempts will work. Test your ideas under the assumption that they won’t (in fact, most won’t). Rather than getting frustrated about the results, leverage the outcome as a learning opportunity. Ask yourself what worked, what didn’t, and most importantly, why? Then keep trying and experimenting.

I also realized that no one really cared whether I made an image or not. Ever. If I stopped photographing, the world would still turn. Oh sure, people might get excited to see what I’m up to on social media when I post a photograph. After they click the Like button or leave a comment—which takes, what, all of three or five seconds?—they move on to other things. Nobody watches us that closely. The only person judging whether we are good enough is us. And if no one is as invested in our work as we are, then why can’t we all photograph whatever we want without worrying about what anybody else thinks? We can dance as if no one is watching, because as the idiom goes, no one actually is.

You get one chance at this life, so fill it with activities and photographs you love. Only one person in the world can connect with it in the way that you can, and do. Shoot iconic scenes if it brings you joy. Shoot unknown scenes of the wild if you wish. Shoot ice on the side of a window if it moves you. Shoot bubbles, or mushrooms, or butterflies if it makes you squeal with delight. Make work that inspires you, excites you, scares you, makes you laugh, makes you cry. Plow through the fear of meeting your own or others’ expectations. After all, you have to live with the photographs on your hard drive, not me, not anyone else. So why not make the type of art you love? To get into the flow state, we have to free ourselves from distractions, including the ones we make-up and hold onto in our own heads.

After I realized how stuck I was that winter in Acadia, I began researching where new ideas came from, and happened upon a description of the four-step Wallas Model of Creativity (oh, the irony!). Creativity experts aren’t certain how the “aha!” moment occurs, that moment of sudden insight, but they do agree on how to encourage it: preparation, incubation, illumination/inspiration, and verification. I translated their terminology into how it applied to my photographic approach:

- Preparation: Fill your brain with knowledge and ideas.

- Incubation: Visualize your picture before you make it.

- Illumination/Inspiration: Relax and encourage the “aha!” moment on location to create images.

- Verification: Critique your image and refine your vision.

Creating fresh photographs, then, relies upon the first step—feeding your brain. With this in mind, I turned to expanding my experiences beyond simply snapping the shutter or visiting beautiful locations. Learning about fluid dynamics helped me understand how water moves and enabled me to find new subjects to photograph in Acadia’s brooks. Taking adult ballet classes allowed me to compare receding waves on Sand Beach to the slow, deliberate adagio I performed in the dance studio. Painting Monet’s Lily Pads taught me how to see relationships between visual elements and become one with lily pads at The Tarn. Studying and writing poetry increased my vocabulary and intensified my sensory awareness, which gave me more fodder to work with when visually expressing metaphors in places I have now sampled for over 450 days since 2009.

These are all examples of conceptual blending, the notion of making associations between unrelated ideas to create something new. I described in detail in my post, It Takes Two. So long as you continue to grow as a human being, you will never run out of material to use in your creative photography process.

So when the idea of picking up your camera feels too daunting—ask yourself, “What would be fun to do right now besides photography?” After all, experiencing the flow state is not limited to photographic endeavors. Instead of forcing yourself to make images, cross-train your brain with other activities to feed the creative process. Trust that the knowledge you collect through new experiences will be useful as input to your photographic practice at some point in the future—without knowing, or caring, when. As Ansel Adams said, “You don’t make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved.”

In the field, you can challenge yourself with forced conceptual blends, which brings this normally subconscious process into consciousness. This exercise uses the existing information in your brain to connect with the landscape in new and different ways. Ask yourself what you enjoy doing outside of photography and come up with a gerund, a verb ending in “-ing” to represent that activity. Cooking. Hiking. Reading. Combine it with a single-word noun, an object in the landscape you might find. Rock. Water. Tree. Then make as many photographs of that combination as possible. Cooking rock. Hiking water. Reading tree. Challenge yourself to define how these two seemingly unrelated things connect with each other, literally and metaphorically. By embracing divergent thinking (developing numerous solutions) versus convergent thinking (preconceiving one best solution), you’ll release the pressure to “get THE shot” and end up on an enjoyable photographic treasure hunt. Make sure you relax your prefrontal cortex, though, as it will attempt to filter your ideas by labeling them “ridiculous.”

When you run out of ideas with one combination, change one or both words. Cooking tree. Knitting water. Paddling leaf. The possibilities are literally endless!

In approaching photography with an open mind, a positive attitude, a focus on learning vs. results, and no expectations, I started to make photographs that excited me—and of subjects and stories I could have never imagined previously. Our creativity does not turn on only at sunrise and sunset. It incorporates, but does not depend on “good” light, a pretty scene, or other external conditions. We shouldn’t judge whether things are happening in a location. We make them happen. We bring the creative juice wherever we go whenever we do. What can you create with the cards you’ve been dealt? If you believe in yourself, trust the creative process, and value all opportunities equally, you’ll get to that magical flow state more often—regardless of whether you ever make an image.

Be well, be wild,

~Bubbles

Have a question about photography, art, and/or the creative life? Need some advice? Send your question to Dear Bubbles at colleen@colleenminiuk.com to be possibly featured in a future column post. (If you’d prefer a different display name than your real first name, please include your preferred nickname in your note.)

4 Comments

Georgi

Very well said. I will re-read this to as there is a lot to take in. I particularly liked the simplicity of the four points of the photography process and the connection with the “flow”. Thank you.

Pingback:

Sarah S

Thank you so much for this. It was inspiring and illuminating, and just what I needed!

Bubbles

So great to hear, Sarah! Thanks for reading!