Thawing Brain Freeze

Dear Bubbles:

Sometimes, I get so overwhelmed when I visit a place, I freeze up. I think I see so many pictures, but I can’t figure out how to take a photograph of anything. So I don’t. I don’t even know where to start. Has this ever happened to you? If so, how did you handle it?

Discouraged

Dear Discouraged:

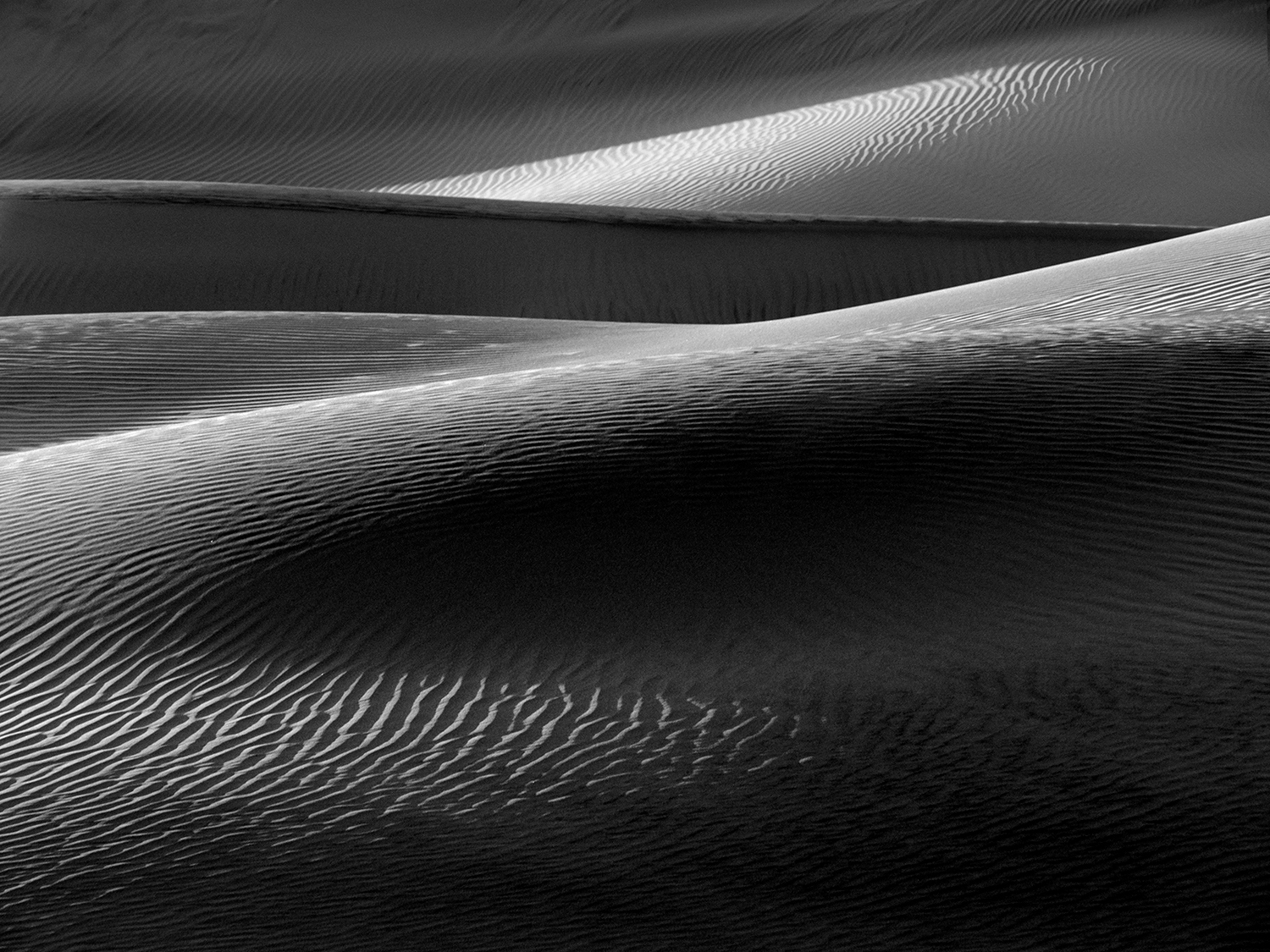

Indeed, this happens all the time to me, especially in places I love visiting and with subjects I fall in love with—like bubbles and waves and sand dunes, oh my! I can get so captivated by awe and beauty, sometimes, I can hardly breathe or believe my own eyes. It happens so frequently, I’ve come to expect it, welcome it even. I live for those moments where the world stops me in my tracks and makes me appreciate my existence.

But my response to feeling overwhelmed hasn’t always been a positive one. Early on in my career, my emotions of amazement and wonder were drowned out by frustration. On location, I could see the beauty “out there.” And I knew millions of photographs existed. Knowing this led me straight into analysis paralysis. I couldn’t decide what I wanted to photograph and where I should stand and what lens I should use and what aperture and should I use a filter and oh my god the light is happening and I’m not ready! GAH! By the time I’d make a decision, the moment—or my enthusiasm for it—had passed. Then I’d get more frustrated because I just had this amazing experience, and I had completely blew it. It triggered FOMO, or “fear of missing out.” What a bad scene that was! Yikes! I didn’t take up photography for this.

When we perceive there to be too many choices in a decision, we experience what researchers call the “Paradox of Choice.” Instead of deciding, we freeze. It happens to me in the grocery store when I stare at the 5 different flavors of pie. It happens when I’m trying to choose a campsite at a campground. It happens while standing at an overlook at the Grand Canyon.

Early on, I thought that as I acquired more knowledge and practice with photography, my camera, creativity, and how my two marbles in my brain worked, I would learn how to make photography-based decisions more easily. It certainly has helped with things like camera functions and photographic techniques (to the point where I don’t even think of them). We can get faster, more accurate, and powerful in our decision-making abilities through experience and expertise. Possessing wisdom and skills, though, can present even more options and even more possibilities especially in a creative space that knows no boundaries. When we know what all the overlooks look like at the Grand Canyon, it can make picking where to photograph at sunset even more complicated, right? (At the grocery store, it’s a lot easier. I just buy all the pie.)

So how do we handle analysis paralysis as photographers? I’m a happy thinker and an overanalyzer by nature, but I no longer let indecision in the field get the best of me. Here’s how we can harness that energy to help us thaw that brain freeze:

Read The Paradox of Choice: Why Less is More by Barry Schwartz. The book does not address analysis paralysis in the sense of photography. That said, it’s a fascinating read about this human behavior, why we do what we do, why it makes us anxious, and how we can manage it in our everyday lives. Simply understanding this natural response made me feel calmer.

Recalibrate your expectations. It is said that expectations are the killer of joy—and it sounds like it’s killing yours. The fastest way to not make a photograph is to set out looking to make a photograph. Instead of expecting you’ll make photographs upon your arrival, embrace an autotelic approach. Chose to do things for their own sake with no expectation of any end goal or result. Simply enjoy the moment as it’s presented to you. I do not go on photo shoots. I do not look for photographs to take. I go for a walkabout, hike, paddle, or drive, and my camera happens to tag along to help me highlight important-to-me moments along the way. I carry no expectations whatsoever of making an image, let alone a good one. This slight, but critical, shift in perspective relieves the pressure to achieve. If my experiences say anything—and this is coming from an overachieving perfectionist—believe it or not, by reducing your expectations, by focusing on something else besides your productivity, you’ll become more productive. And if you don’t bring home any images on your memory card, that’s OK! You don’t have to make an image to have a great time! You can still record the memories in your brain.

Soak it all in first. Take a second to acknowledge how amazing it is that you are in this exact place and time. (If you tend to feel time stressed, arrive a few minutes early to do this so you don’t feel rushed and compelled to shoot-shoot-shoot right away.) Look at where you get to be! Everything you’ve done in your life has led you here. And what you’ll experience in this moment will shape how you see the future. How awesome is that? Maybe you’re not feeling awesome. That’s OK too. Welcome whatever feelings arise. Feeling overwhelmed is a completely normal response to experiencing something for the first time or seeing immense beauty. It’s also completely normal to worry about what equipment to use, which settings to apply, keeping things in focus, etc. Or maybe you have limited time to explore. Or maybe the light isn’t what you expected. Whatever is causing your emotions, give yourself permission and space to accept them and feel them. Don’t judge them. They are valid. Take a few deep breaths. Once the excitement and nervousness subsides, you’ll be able to redirect your mental energy towards observing, creating, and problem solving—all necessary steps in the creative process. But expressing gratitude and centering yourself will get you on the right path. (For more tips on how to stop overthinking and calm yourself down, read my “Mind Your Monkey Mind” post.)

Start anywhere. It doesn’t matter where you start, just that you do. All the photographic ideas swirling in your head when you see a place are all right answers. Every single one of them. Pick one idea to start with. It doesn’t matter which one. Just because you start somewhere doesn’t mean you have to end there. See where this one idea takes you. If you still can’t decide, turn your camera on, take your lens cap off, point the camera somewhere, anywhere, and then shoot something, anything. Then…

Ask yourself what you like and don’t like about your frame. If you like something, anything, in your frame, keep it and emphasize it. Make whatever “it” is take up more space in your frame by modifying your perspective, getting closer to your subject, and/or changing to a more telephoto lens. Then ask what you don’t like about your frame. Whatever that is, get rid of it. Reduce its dominance in the frame, hide it somehow behind other elements, or eliminate it from your frame completely. For this question/answer “game” to work, you must dig deeper than “I dunno, I just like it” or “I just don’t like it.” You must have a specific opinion. Is it the shadows creating texture? The bright light in the center of the photograph? The relationship between the tree and the rock? The distracting branch on the edge of the frame? Be specific. Fix it. Make another frame. Ask yourself what you like and don’t like about this new frame. Keep repeating this process until you get to “I absolutely love everything about this photograph.” And you will get there! I’d argue that, if you embrace these “like/don’t like” questions, you could start by making a picture of your foot and eventually end up with a photograph you’re proud of. Now, that said, if you truly do not like a single thing about your frame, start over with a different composition. Don’t stress about finding something better. Don’t overthink it while you’re frustrated. Literally, anything else will do–like your other foot!

Be methodical about how you approach photographing a scene. Having a framework in which to operate can tame anxiety. Putting together a checklist to follow can help. What do you need to remember when you’re out there with your camera? What do you often forget? Figure out an approach that works best for you, and go with it. If you practice your preferred sequence of actions over and over, and fine tune this checklist along the way, your process of observing and interpreting the scene visually will become second nature (and you won’t need a checklist AND when you’re faced with a multitude of variables, as we are, you will know how to address them without feeling overwhelmed.). I have never photographed from a checklist, but after doing this for 22 years, my approach is pretty routine. At a high level, my checklist might look something like this:

- Notice what I’m paying attention to (through mindfulness and taking inventory).

- Define a visual message—I often title my photographs before I shoot.

- Pick the appropriate lens.

- Decide where to stand and/or set my tripod.

- Arrange the visual elements within my frame to support my visual message.

- Incorporate light, shadow, and tonality to create the illusion of depth and the mood/meaning I seek.

- Get out my filters, reflectors, diffusers, etc. to help balance the light more effectively.

- Set the aperture to achieve my desired depth of field.

- Ensure my shutter speed and ISO are fast enough (or slow enough) to achieve my message.

- Set my focus point.

- Check my histogram after I shoot to adjust exposure, if needed

- Ask what I like/don’t like about my photograph.

- Make necessary adjustments.

- Figure out what else could I do with this scene (I mean, I’m here, I’m set up, and I’m in love with the subject or scene, so why only make one image?!)

- Eat pie to celebrate (any of the five flavors will do!)

Make a lot of bad photographs—on purpose, for growth’s sake. You’re better off making a bad picture than no picture at all. If you play the “what do I like/not like about my picture” game that I described above, at the very least, you’ll discover a deeper understanding of your preferences and goals with each click even if the frame doesn’t turn out to your liking. If you make no image, you remain stuck in the same place. Which would you prefer? To try and fail or fail to try? I make way more bad images than I do good ones. I publicly share 3% of my images. Those are the ones I really like. That’s not a typo. Three percent! That means 97% of my frames were experiments, screw-ups, train wrecks. Look, we do not track batting averages in photography. It might take two images or two hundred to figure out what you like and don’t like about your image and to express your visual message successfully. Who cares? No one’s counting (other than you). Besides, they put the Delete button on the back of the camera for a reason. Use it. But learn something new about yourself, your craft, and/or the world around you before you do, and you will become a better photographer over time.

Accept FOMO. No matter how much knowledge, skill, and experience you have, recognize that by making a choice, you are always missing something. There are a gazillion paths you could take out there. Could be something better. Could be something worse. But like making bad images, you’re better off making some choice than no choice at all when faced with uncertainty. Don’t let fear of something better out there hold you back. Pick an idea, any idea. If you’re having fun or learning, keep going. If you’re not having fun, go find greener grass. (Because maybe it’ll have dew drops–BUBBLES!–on it?!) You have the power to course correct, if you’d like, after you’ve made a decision.

Be kind to yourself. Remind yourself why you got into photography in the first place. Photography is supposed to be fun! You didn’t take up photography to feel miserable, frustrated, and disappointed. No one does. Go easy on yourself. Recognize you’re doing the best you can. And sometimes it works out; sometimes it doesn’t. External factors like light, weather, seasons, etc. aren’t within our control. Our internal responses to them, however, are. Chastising yourself while you’re struggling will only make things harder on you. Don’t get in your own way. Feeding yourself more positive encouragement will lead to less pressure, more relaxation, and a more enjoyable experience. Doesn’t that sound more appealing than going home frustrated and discouraged? Remember, thoughts are just thoughts. They are not reality. If we can make up negative narratives, we can make up positive ones just the same. Choose wisely.

This was all long for what businessman and author W. Clement Stone summed up best: “Thinking will not overcome fear but action will.”

So melt that analysis paralysis. Go forth and create!

Be well, be wild,

~Bubbles

If you liked this post, please consider supporting Dear Bubbles either through a monthly contribution through Patreon or a one-time donation through Buy Me a Coffee. Learn more about both at https://dearbubbles.com/support.

Have a question about photography, art, and/or the creative life? Need some advice? Looking for inspiration? Send your question to Dear Bubbles at [email protected] to be possibly featured in a future column post. (If you’d prefer a different display name than your real first name, please include your preferred nickname in your note.