Getting In Your Head

Dear Bubbles,

What goes through your head when you make a photograph?

Adam

Dear Adam,

Why, this has to be the scariest question we’ve ever had on Dear Bubbles!

To help answer your question, I started paying closer attention to the stream of consciousness running through my head as I created my images. During a recent outing to southern Utah, I made it a point to verbalize my contemplations aloud so that I could keep better track of them. Thankfully, I was alone most of that time…

Of course, in doing this, I must warn about the Observer Effect. According to science, anytime you observe something, it changes the behavior of that something. Like the Schrӧdinger cat thought experiment which describes “superposition”—the idea that two distinct phenomena coexist simultaneously—I am likely thinking about absolutely nothing and everything in the multiverse at the same time until my thoughts are observed by an external source. So take my answer with a grain of salt. Who knows what actually goes on with the two marbles in my brain? Challenge accepted nonetheless!

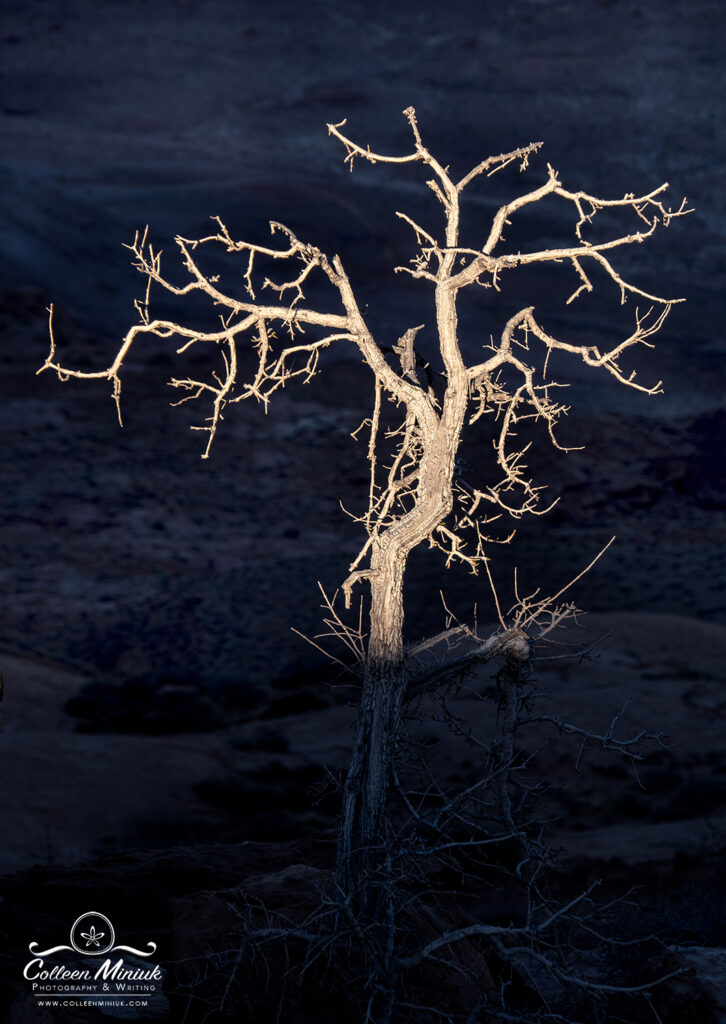

Most of the time, as it was in the creation of the photograph on the right while I walked along the rim of a canyon aimlessly but actively observing, it’s as simple as “Look at that light! It looks like Medusa! Get the camera!” Click! Maybe I do a little happy dance afterwards. Maybe I take another shot or two or ten from a slightly different angle. But typically it’s truly that anti-climactic.

Most of the time, as it was in the creation of the photograph on the right while I walked along the rim of a canyon aimlessly but actively observing, it’s as simple as “Look at that light! It looks like Medusa! Get the camera!” Click! Maybe I do a little happy dance afterwards. Maybe I take another shot or two or ten from a slightly different angle. But typically it’s truly that anti-climactic.

Other times, like when I made the image at the head of this post while camping along a different canyon on the same trip, it sounds more like this:

“Look at that light!

How lucky am I that this is how I get to spend my Monday evening.

God I love my life.

Don’t trip on the rocks and crack your head open.

No one is around for miles to help you if you bleed out.

I can’t wait for my Wilderness First Responder recertification class in two weeks.

I’ll save myself!

Don’t forget to find your WFR card from last time to give to the instructors.

(Types reminder on iPhone.)

Is that a rattlesnake under that rock?

Oh hi little lizard. Carry on, I won’t hurt you.

(Break out into the “Flora’s Secret” song by Enya: “Lovers in the long grass…”)

What do we have here?

When I rafted this stretch of the Colorado River with my dear friends last year, I wanted to see it from the top.

And here we are! Woot woot!

It kind of looks like snake slithering through the sand.

Do I really want the river cutting right through the center of the frame?

Yeah, the row through there was so peaceful.

(Changes camera orientation from vertical to horizontal to convey more peacefulness.)

I wonder how Jen and Michael are doing. I’ll text them when I get service.

What if I move a little to the left?

What if I move back just a smidge?

Don’t get too close to the edge.

Don’t fall off the cliff.

Let’s start with the wide-angle lens.

Gah! My battery is dead.

Remind me to charge my batteries after this.

(Inserts new battery.)

(Tripod slumps slightly askew on its own.)

I can’t believe I’ve forgotten to tighten my tripod leg again.

(Tightens tripod leg.)

It’d be amazing if that V-shaped cloud moved over that plateau a little more.

A little more…come on, cloud!

Wait for it.

Wait for it.

I’m hungry.

Where do you want to camp tonight?

Right here seems good.

Do you feel like writing or painting or staring off into the stars tonight?

Painting!

I could try to paint that scene from yesterday.

(Changes my aperture.)

Hi raven, thanks for stopping by. How are you today?

(Light lights up the cliff.)

Yay!

(Clicks the shutter.)

How’s your histogram? Check your histogram. (While shaking my head and pretending to be a bobble head doll. Those who have been on my workshops will get this joke…)

Gah! Too bright.

Subtract light.

Perfect.

Except I don’t like that corner.

I could warp it…

Warp it, baby! (Clap, clap, clap.)

Eh, that’s just more time behind a computer.

How about I just shimmy a little to the left?

Shimmy, shimmy, shimmy!

(Begins spontaneous dancing involving shoulder shakes.)

Don’t fall off the cliff.

What was that noise?

Was that a coyote?!

Man, I’m really hungry. I should grab a bar from the truck.

(Looks up time on iPhone.)

How is it already dinnertime?

What do you want for dinner?

(Clicks the shutter.)

(Checks the histogram.)

Yeah, I like that. I like that a lot.

That worked. Cool beans.

Oooooh, look at that over there…

Dinner can wait.

So can painting.

I love this river.

The coyotes are singing again.

God I love my life.”

This may sound like a bunch of insane gobbly goop—and it is! But it’s my insane gobbly goop, and I love and embrace it nonetheless. While this narrative is representative of my current process, it hasn’t always been the case.

Had you asked this question within the first 12 years after I started photography, my answer would have looked very, very different. The narrative would have focused more on “How slow does my shutter speed need to be to blur the water?” and “Which filter should I use to darken the sky?” and “No, really, if I don’t get the right depth of field after this 744,231st attempt, I’m gonna poke my eyeballs out.”

And then, after about 12 years of thinking, thinking, thinking, and thinking hard about photographic technique and camera functions involving exposure, composition, and lighting, it all clicked into place (pun intended). I stopped thinking about it entirely—and haven’t thought about it since unless I’m trying to learn a new skill. And! I have yet to poke my eyeballs out. (Note how little of the long internal conversation above pertains to photography.)

Author Malcolm Gladwell popularized “The Ten-Thousand-Hour Rule,” a 50-year-old concept scientists Herbert Simon and William Chase developed that suggested one needed to invest approximately 10,000 hours of dedicated practice in order to master a complex task. While experts still like to argue about whether the appropriate number is 10,000 or 50,000 or 10 hours, the point still stands: one must practice a lot for something to become so ingrained in one’s head that it becomes second nature. That “a lot” for me and my photography just happened to equal about 12 years, half of which I was a full-time freelance photographer selling my work. (Yep, that’s right. I really did quit my day job not understanding the half of it…)

For those of you who have had a driver’s license for some time, how often do you now think about the mechanics of driving a car? I’d guess you don’t most of the time. Compare that to when you first started driving. If you’re like me, you probably thought obsessively about where the button to roll down the window was and how to shift the car from park to reverse and how to give the curb enough space so you didn’t run over it. Because you’ve repeated the same motions over and over and over and over and over and over and over again, you probably can roll the window down without looking at the button and change into reverse without looking at the gear shifter. (Hopefully you don’t run over curbs too often either.)

The same goes for photographic technique and camera functions. If you feel like you aren’t sound in the basics of things like incorporating exposure, composition, lighting, etc., it’s not only OK, but rather essential that you’re thinking about them over and over and over again when you’re out in the field or visualizing being out in the field. (To read more about the power of visualization, visit my “Picture Your Picture” post at https://dearbubbles.com/2021/02/picture-your-picture/)

I spent a solid 12 years believing that if I’d just go out to some remarkably beautiful place, I’d make better images. On occasion, I’d get lucky enough with the composition, perspective, and lighting conditions to pull off a sellable image without the requisite knowledge. Seeing new places always felt exciting, but it was not necessary to travel far and wide in order to learn the fundamentals. In between my work travels, I’m currently studying up on concepts like notan, photo montage, and international camera movement at home then practice the ideas with cut flowers on my kitchen counter, shadows from my blinds in my bedroom, and moving tree branches in my yard.

If you wish to make progress on your photography skills today, go out on dedicated practice sessions in your backyard (or front yard or your local park) where you don’t have a lot of time and money invested in making a remarkable photograph. Eliminate the expectation to perform and focus entirely on your learning and growth. Shoot your grass or fence or tree bark over and over and over again until you understand how to switch drives modes, incorporate the tonal range, and control depth of field—among all the other things involved in creating a photograph—so well you can do it with your eyes closed. Talk yourself through each step. Think about what you’re doing and how and why. If you make a great image in the process, great. If not, great. If you mess up, great: learn from it and try again.

As you become more proficient in the tools and techniques, you’ll find yourself thinking about it less and less. “Mushin” is a Zen Buddism term for “mind without mind.” This mental states occurs when your mind is free of distracting thoughts, emotions, and stress. When you intentionally stop thinking about something, intuition kicks in. In order to trust yourself in this space though, you have to put in the time practicing. Then you have to trust yourself to trust yourself.

While developing new skills, all of us will go through a teetering transition phase where we think we know enough but are not yet confident to have faith in our abilities. One minute, we think we totally got this! The next minute, we don’t.

This is where my negative self-talk tries to creep into my head. Through mindfulness (i.e., paying attention to what I pay attention to), I’ve learned to recognize any non-supportive voices in my head and chase them off. Negative, degrading notions like “You suck” and “How come you can’t make a better image” will do absolutely nothing to help you progress. I also disregard thoughts associated with expectations like “Man, if only I had better light” and “There’s gotta be a photograph here somewhere.” Forcing a photograph is the fastest way to prevent a meaningful one from happening. Also, holding on to expectations of things we can’t and don’t control can lead to disappoint and frustration. As you work through your process, and perhaps travel to more exotic locales, become a careful observer of your thoughts.

For those of you thinking “But, but, Bubbles. Maybe I do really suck,” first, you don’t. And second, read (or reread) my earlier column “The Art of Not Sucking”: https://dearbubbles.com/2020/01/the-art-of-not-sucking/ . Then third, remember your thoughts are only thoughts. They are not real. If your brain can make you believe destructive things, then you can make your brain make you believe encouraging things just the same. Change your narrative from “I suck” to “Could I improve? Sure. But I’m sure proud of myself for learning [XYZ] today!” Through the course of a lot of recent life experiences, I’ve come to see being grateful for what you have, and not sad for what you lack, leads to fulfillment in photography and life.

Another mental head game I’d recommend to encourage mushin is switching your attitude away from “going on a photo shoot/outing” and into “playing” and “exploring.” Renowned scientist Albert Einstein, and others like him, believed creativity couldn’t be forced. It requires a dose of spontaneity, an instantaneous spark. He said “the act of opening one mental channel by dabbling in another” is how we best generate imaginative ideas. It’s called “combinatory play” (and also “effective abstention”). Science has since shown that certain parts of the brain fire up only when you’re relaxed. How many great ideas pop into your head while showering? Exactly.

While it may sound like semantics, do not go on photo shoots. Trick your brain into believing you’re doing something else. Then do literally anything else besides go out and try to make a photograph. Go on a hike, a bike ride, a drive, a paddle, an exploration, a yoga practice, a birding expedition, a hopscotch, a treasure hunt, or my personal favorite, a bubble quest. Call it whatever you want. Play! Wander! Be curious about the world around you! I know it sounds counterintuitive, but by distracting ourselves and letting your brain mindlessly wander (as mine was doing in the lengthy word chain above) in unrelated things beyond photography, we free up energy in the parts of the brain responsible for expressing creativity.

So while it may seem like I have attention issues from the conversation above, giving my brain the space to wander, to do whatever it wants to do while I’m out there playing and exploring (so long as it’s in a supportive manner) is quite intentional. Deliberately not thinking about photography helps me make more deliberate photographs. But in order to not think, I had think about these skills incessantly at first. The morale of the story? Get in your head, then get out of it.

Now, if you ask this same question of me 12 years from now, I’d bet a lot of money that my answer won’t be the same one I’m giving you today. Maybe by then, I’ll be incorporating Jedi mind tricks while doing a one-handed handstand while blinking my eyes to snap the shutter. Here’s hoping! That sounds like all kinds of fun, doesn’t it? I’ll start researching and practicing it now…

Be well, be wild,

Bubbles

Have a question about photography, art, and/or the creative life? Need some advice? Looking for inspiration? Send your question to Dear Bubbles at [email protected] to be possibly featured in a future column post. (If you’d prefer a different display name than your real first name, please include your preferred nickname in your note.

2 Comments

Lynn Wiezycki

As always, I am so excited to read another Dear Bubbles. This one is so on point for everyone! I have shared it with all your fans at the Tampa Bay Camera Club! Thank you, Colleen!

Bubbles

Thanks so much, Lynn! HI to all at the Tampa Bay Camera Club! Keep shooting!